Searching for Greg Ginn

Why is Greg Ginn disliked by so many of the people that should be honouring him?

Art is fuelled by egos. Whether it’s music, film or literature, ego is the driving force.

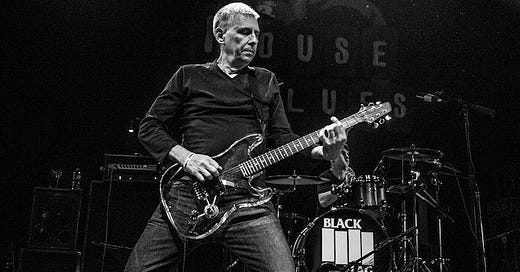

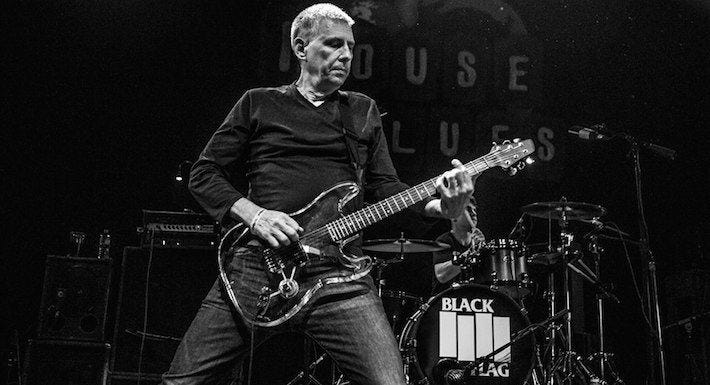

Greg Ginn- the founding member and driving creative force of the legendary hardcore punk band, Black Flag. A man whose work as the Flag guitarist guarantees him a place as one of the most influential musicians of the last 30 years. So influential in fact that Rolling Stone named him among the 100 greatest guitar players of all time.

When Ginn formed Black Flag in 1976 (first known as Panic) with Keith Morris no one would have predicted that he would go on to change the face of underground music. In the blink of an eye Black Flag morphed from a band that sounded a little too much like the Sex Pistols into a snarling, raging beast that became the standard bearer for the burgeoning hardcore scene. Black Flag was more than just a punk rock band, it was the rallying cry for the youth rebellion that was taking place across Suburbia, USA as misfit kids railed against the sterile 80s mainstream culture that shunned them for not fitting into the ideal American middle class family.

Take a closer listen to Damaged, arguably Black Flag’s magnum opus. Made in 1981, Damaged, with its chainsaw double guitar assault and howling vocals, became the blueprint of hardcore punk that nearly every other band would spend the next three decades copying. Thirty years later, Damaged remains the pinnacle to which all other punk bands aspire. Tracks like “Depression” and “Damaged II” are such visceral, seething pits of self loathing and angst that few artists have come close to matching their intensity.

Yet Black Flag’s and Ginn’s legacy extends far beyond one solitary LP. Bored with the hardcore sound he had helped forge, Ginn crammed more musical evolution into the final five years of Black Flag than most other bands could even dream of. Their punk sound grew to include metal, think metalcore before anyone was scene enough to coin the term ‘metalcore,’ before branching off to incorporate jazz and breakbeat elements into their final records.

All the while, behind the scenes Black Flag lurched from one crisis to another. Ginn had to deal with a band line up that was in a constant state of flux, 16 different people played in the band over ten years, police harrassment (stories of Los Angeles police showing up at venues to shut down Black Flag gigs and assault anyone who dared turn up are legendary), a record company that reneged on a deal to distribute their album, tour van robberies, a decade of living in perpetual poverty and a fan base that gradually turned on the group. Considering all the drama that engulfed Black Flag, the achievement wasn’t that they influenced countless other bands, it was the fact they survived as long as they did.

The reason for their longevity? Greg Ginn and his Do It Yourself work ethic. Venues black listing the band? “We’ll book our own tours around the country and overseas.” Record label won’t distribute our albums? “We’ll create our own label and distribute it ourselves.” Not enough people listening to our records? “We’ll tour so relentlessly and play so many shows in two bit dives around the world that Satan himself couldn’t hack our brutal tour schedule.”

Today’s underground music scene owes a great deal to the trailblazing work of Black Flag and their tireless work ethic. Each and every band that organises its own tours and distributes its own records is following the path that Greg Ginn established thirty years ago without the help of little things like the internet or Facebook to help spread the word, instead relying purely on word of mouth, letters, fan zines and flyers.

Clearly, Greg Ginn is an icon of alternative music. A man to whom many extremely wealthy musicians owe their fortunes to for paving the road that would lead them to riches long after Ginn’s time had come and passed. Ginn’s achievements should be celebrated. So why is Greg Ginn disliked by so many of the people that should be honouring him?

“My War, you’re one of them, you say that you’re my friend but you’re one of them.”

The very talents that made Ginn such a trailblazer of underground music- the DIY work ethic, the unique vision and artistic drive- are the same traits that gradually alienated him from everyone around him. Chuck Dukowski, Flag’s founding bass player and most charismatic spokesman in their early years, was kicked out of the band as soon as he began to no longer fit the sound that Ginn was striving for.

The passing of time is hard on everyone but it has been particularly hard on Ginn. While the legacy of Black Flag has grown substantially over the years as the band is more popular in 2011 than it ever was in the 80s, Ginn’s aura has been drastically diminished. The shallow answer for this is the rise and rise of Henry Rollins from Black Flag’s vocalist to poet, writer, actor, spoken word artist and radio DJ has led to some revisionist history that has swept Ginn under the rug. It’s often stated that Rollins joining Black Flag signalled a change in the band’s sound and image becoming heavier, darker and more macho. But it was Ginn who was the catalyst for this shift. Ginn was already moving in that direction and he brought in Rollins because he thought he would suit the sound he was going for. When it came to Black Flag Ginn was always the engine, the steering wheel and the driver, everyone else was confined to the backseat, even Henry Rollins. In reality Ginn’s post Black Flag demise can be traced back to the fall of SST Records.

SST Records was the label that Ginn created in 1978 as a means of distributing Black Flag’s releases, however Ginn’s lofty ambition and prodigious work rate saw the label grow into something much greater. Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr, Husker Du and the Minutemen all got their start on SST and by the mid eighties SST had become the main hub for the underground music scene in North America.

Although the end of Black Flag in 1986 was mourned by few since the band had by that stage fallen into a turgid milieu that left many scratching their heads, Greg Ginn and SST Records seemed poised to continue promoting and nurturing the nascent underground music scene that they’d spent the last decade building. Instead within a few years, thanks to Ginn’s incompetence, SST was reduced to a footnote as it was overrun by upstart indie labels like Sub Pop.

“Beat My Head Against the Wall.”

For all Ginn’s talent at identifying and promoting young bands, he also had an uncanny knack of alienating those same musicians as soon as they began to experience success. Sonic Youth, Husker Du and Dinosaur Jr all left the label citing difficulties working with Ginn and unpaid royalties that had been withheld from the bands by SST. Years later Sonic Youth and other acts would sue SST to reclaim their master recordings and the unpaid royalties they were due.

By 1988 the rot had set in at SST. Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr and Husker Du had all since quit while the tragic death of D.Boon meant the Minutemen were no more. In their place, Ginn signed a plethora of awful jazz groups while his new band, Gone, a prog rock act, never gained any traction and quickly sunk along with the once mighty SST.

The 90s Grunge explosion is the greatest irony in the fall of SST. Despite what Rolling Stone and mainstream media would tell you, grunge didn’t simply emerge out of nowhere. It was the culmination of years of blood, sweat and tears from unheralded musicians like Greg Ginn who established a scene and culture from nothing. It would have been just rewards for SST to cash in on its hard work by becoming a key player in the 90s grunge scene but 1991 it had already fallen into the mire, its title as the premier indie label long since faded.

Today Greg Ginn and SST Records remain a shadow of their heyday. SST infrequently awakens from its slumber to put out another interminable jazz record that absolutely no one cares about while Ginn is occasionally coaxed into an interview about the Black Flag days and the 80s hardcore scene.

Yet despite receding into cultural insignificance, Ginn still has his knack for infuriating the people who would otherwise look up to him. Earlier this year, Ginn, through SST Records, issued a copyright complaint against all users who had uploaded footage of Black Flag live sets to YouTube. Within days the video website was stripped of all Black Flag clips except for a handful that SST uploaded. In an age when musicians use sites like YouTube to promote their work, Ginn’s decision displays a distinct lack of business acumen. How are fans and potential customers supposed to hear Black Flag if they can’t find it on YouTube? No one buys CDs any more and besides, SST discs are difficult to find considering the label hasn’t exactly been keeping their albums in stock. If this was 2001, you could almost forgive Ginn on account of not understanding new technology and its impact on the consumption of music, but this is 2011 and even a disconnected Greg Ginn should be smart enough to see the writing on the wall.

Business and marketing perspective aside, this decision stinks from a cultural standpoint.

Black Flag are one of the most important and influential bands of the last thirty years, their work has shaped the sound of rock music. Forget about the technicalities of copyright laws, this footage belongs to the people. In every art form, whether it’s film, music or literature, there are cultural touchstones that everyone needs to experience. In the field of rock n roll Black Flag is one such cultural touchstone that should be available at all times to all fans, especially today when the vast majority of music is so deplorable that garbage is celebrated and mediocrity is lauded as genius. It seems depraved to think such essential footage could be locked away in a cardboard box somewhere in Greg Ginn’s garage and never see the light of day.

The footage will undoubtedly resurface on some blog or forum, such is the way of the internet but it shouldn’t have to be like that. This is footage that needs to out there in front of the next generation of musicians so they can see what the real stuff is all about. One can’t help but wonder what 1980s Greg Ginn, that young punk who pioneered DIY work ethic to get his music out there, would think if he saw his older, burned out self stepping on kids for daring to share his music?

He’d probably shake his head and mutter;